Why Are Printed Flags So Rare?

Machine sewed, hand-stitched, and printed flags all have their own value and role in manufacturing and American history, but why are printed flags so special? Why don’t many early versions survive today? How exactly were they made?

WHAT DOES ‘PRINTED FLAG’ MEAN?

First, let’s explore what a printed flag is. As opposed to an American flag with several different colored pieces of material stitched together to form the Stars and Stripes, a printed flag is made of a single cut of cloth. In the early days of the United States, the country lacked not only the technology to efficiently dye multi-colored cloth, but also the finished materials to print onto. American flags were not household items until about the Civil War, but those that do date to the beginning of the 19th century were typically hand-stitched. Once printed flags were produced, they were made in large batches for the public, however, that doesn’t mean that they are common today.

WHY ARE THEY SO RARE?

Since they were designed for short-term use, parade flags were more often made with cheaper, more readily available materials such as muslin. Muslin is a plainly woven, thin fabric that was inexpensive to produce. War often caused wool and cotton shortages and in 19th century America, war was abundant. This thin, alternative material was both easier to find and perfect for short-lived celebrations. Unlike the hand-stitched flag a family member spent months on or one they saved up to purchase from a seamstress, these printed flags were always regarded as ephemera and not purposefully saved. The material and short-term use worked together to ensure not many of these printed flags survived compared to the thousands that were produced. The fact that any survive at all is against the odds.

HOW WERE EARLY FLAGS PRINTED?

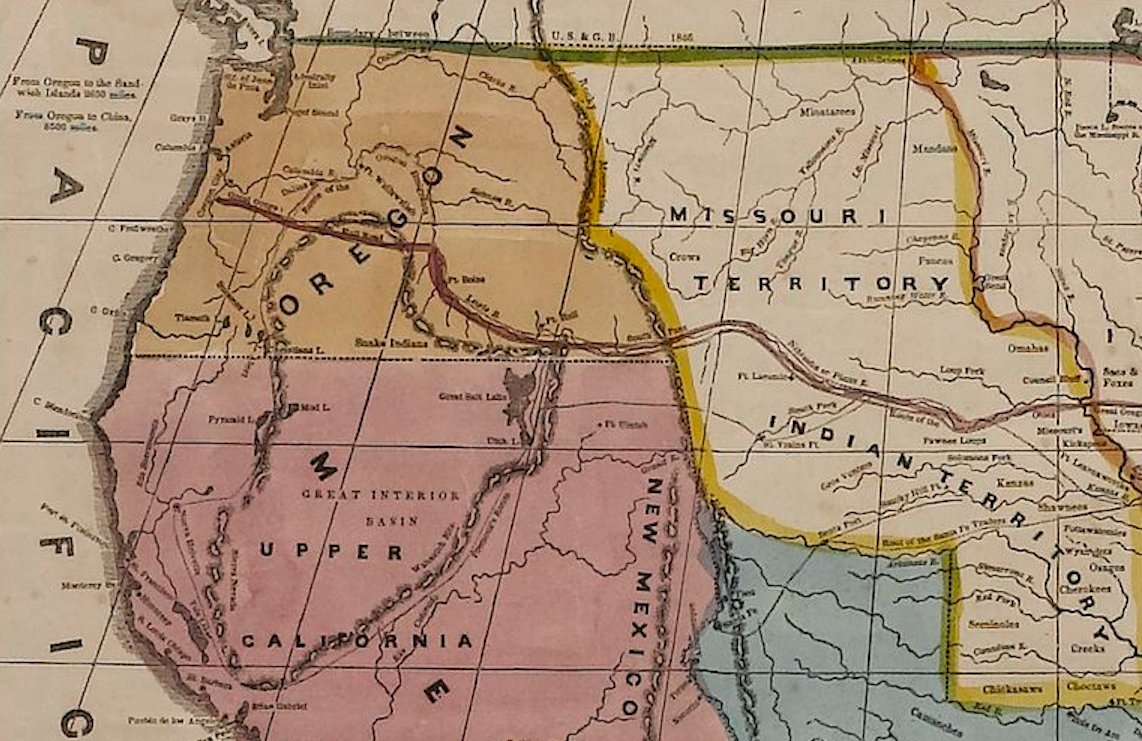

Until the mid-19th century, many American flags were made at home or in small seamstress shops. It wasn’t until the eight years the 26-star flag officially flew that the first printed parade flags emerged. Before that, materials and technology limited mass production of American flags. America exported raw cotton, but finished textiles were produced in Europe and the technology to produce it en-masse was a closely guarded secret. However, in 1813 Cabot Lowell smuggled the highly protected knowledge of the cotton spinning machines out of Great Britain. Suddenly, America could produce finished textiles domestically, lowering the cost of the common flag material.

Once the material became available, makers could invest in textile printing. One such method available in the early 19th century was roller printing. Likely how our 26-star flag was produced, roller printing was largely based on copper plate printing techniques. An engraved copper plate was attached to a cylinder and inked. Then the cylinder was rolled over a continuous strip of textile. Afterwards, the material was cut and trimmed before being attached to a wooden stick. The bolt presented here did not ever complete this process and remains uncut. It likely only survives because it was left unfinished and never sold to the public.

Thanks to advances in technology, a new method overtook roller printing in 1870. The clamp dye process, invented by Edward Brierley and adapted for American flags by John Holt in 1870, greatly expedited the textile printing process and allowed for an explosion of flag production. This process involved metal strips with rubber lining that clamped down tightly onto the textile, blocking ink in those areas as the sheet was dipped in ink. Another clamp with a star pattern was used to create the canton and suddenly parade flags were much more abundant. During the centennial celebrations, many 38-star flags were produced in this manner.

Despite the elevated production, these parade flags were still often considered short-term products. Those that survive today are both fragile and rare. Printed flags display some wonderful star patterns and have a certain celebratory nature that can still be felt today.