How the Washington Monument Came to Be

The Washington Monument stands as a tribute to our first president, George Washington, and is a focal point of the nation’s capital. The building of the Washington monument was not an easy venture, however, and the struggles and triumphs of its construction tell a unique story. Read more about how the Washington Monument came to be in this week’s blog.

The Nation’s Capital: A Center Stage for the Washington Monument

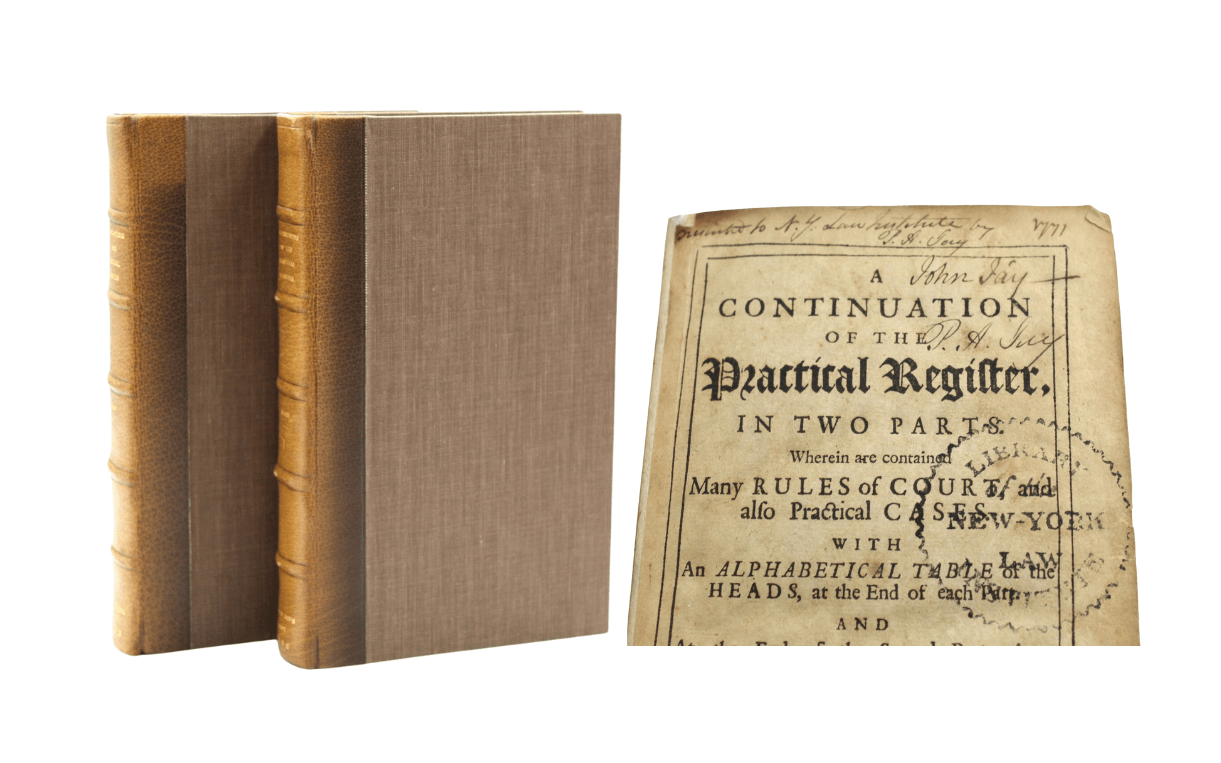

Washington D.C. was officially named the capital of the United States in 1790. Since then, people began imagining ways in which to honor the new country’s first leader. Upon the capital’s establishment, Pierre L’Enfant was hired to plan the “Federal City.” He designed streets, buildings, and open spaces, all the while leaving open one spot for a spectacular monument. The National Mall, as it is known today, was created to be accessed from all sides, so that the nation’s capital would be considered an accessible location for all that visited. At the center of this space, located between the White House, or “President’s House” as it was then called, and the Capitol was the space for a future monument to President George Washington.

Detail of original Plan of the City of Washington showing the location of the future Washington Monument

Pierre L’Enfant’s design for the City of Washington came to fruition in 1792, with a little help from Andrew Ellicott who took over the project after L’Enfant was dismissed. As it appears in the first official printing of the Plan of the City of Washington, the space for the monument was left untouched and unnamed. In fact, even with the initial idea for a monument in place via L’Enfant’s design, the actual plans for the monument didn’t even take shape until the 1830s.

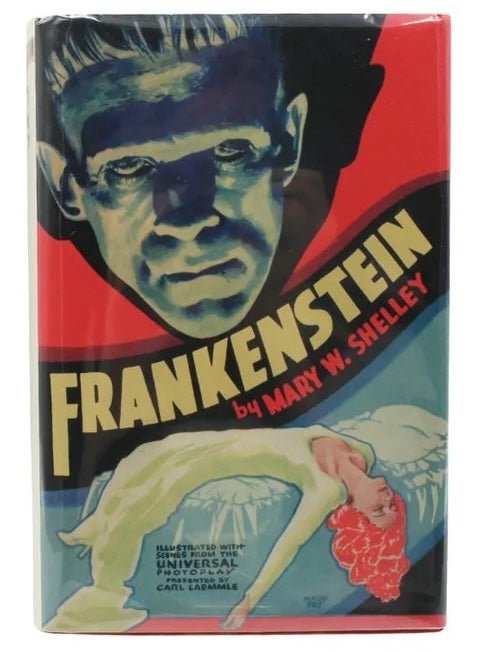

The first individuals to put the Washington Monument plans into action made up the Washington National Monument Society. In 1833, this private organization set the standard to form and fund the first monument to George Washington and the American presidency itself. Their goal was to produce a monument that would be “unparalleled in the world.” The society spent the next decade and a half raising funds for the project, and relied on both private donations and funds raised through the sale of materials such as this 1846 Design of the Washington National Monument Lithograph.

The society requested project designs for the monument and ultimately decided on a plan by American architect Robert Mills. Mills’ design was unique and grand. Much of DC’s architecture was Greek or Roman inspired--take the Capitol for example with its dome resembling a Roman cathedral. However, Mills’ design stood in stark contrast to these European influences. Instead, his drawings for the Washington Monument resembled an Egyptian design called an obelisk, which was at one time a symbol of power and honor for pharaohs.

Detail image showing the original plan for the Washington Monument

In addition to the unique shape and symbolism, the Washington Monument as designed by Mills was to include grand columns at the base, encircling the wide and thick obelisk. The entire building was to be 600 feet tall, with a total of 30 columns that measured 100 feet tall. Ultimately, the grandiose design was approved by the Monument Society, as they saw that it was important to immortalize Washington with a building that was worthy of all that he had accomplished.

By 1848, the Society had raised enough funds to support the construction. Going with Mills’ plan, they laid the first stones of the monument on July 4 with over 20,000 people in attendance. “Builders commenced work on the blue gneiss foundation, an 80-foot square step pyramid. With the substructure completed, the builders then proceeded to the above-ground marble structure, 55 feet, 1.5 inches square at the base, using a system of pulleys, block and tackle systems, and a mounted derrick to hoist and place the stones, inching the structure skyward” (NPS, 2019).

The construction was going well for quite some years. In keeping with Mills’ original plans, the base of the building was wide and sturdy. However, the project was also exceedingly expensive. By 1854, the project hit a bit of a road block.

A while into construction, the Washington National Monument Society underwent a change in administration. A political party named the “Know-Nothing Party” threw a wrench in the plans when their members infiltrated the Monument Society. This party was founded on the basis of keeping Catholics and immigrants out of politics, and their influence in the Society was detrimental to the project of building the monument. The change in administration caused the Society to go bankrupt, with donors being alienated and pushed out of the project. This turn of events left the monument at only a quarter of the way finished, with only 156 feet built of the projected 600 foot monument.

When the Civil War started, the Washington Monument construction was not a priority. The monument stood unfinished from 1854 all the way through the war and afterwards. It was not until the United States centennial in 1876 that real change took root. In 1876, Congress took on the duty of constructing the monument. The project became the responsibility of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, led by Lt. Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey.

Over two decades later, picking up where the Society left off was not a simple task. To continue building upwards, the masons needed large quantities of stone. However, the quarry near Baltimore that originally provided the stone for the monument was no longer available. “Seeking a suitable match, the builders turned to a quarry in Massachusetts. However, problems quickly emerged with the quality and color of the stone, and the irregularity of deliveries. After adding several courses of this stone from Massachusetts, still recognizable by the naked eye today as a brown-streaked beltline one-third of the way up the monument, the builders turned to a third quarry near Baltimore that proved more favorable, and used that stone for the upper two-thirds of the structure” (NPS, 2019). This change in stone is still quite apparent today, and speaks to the difficulties that the makers and masons faced in picking up where the last builders left off.

Detail image of the Washington Monument, completed by this time in 1921

Many of Mills’ original plans were thus scrapped in exchange for a sleeker design. The height of the monument was adjusted, the columns design at the base was rethought, and the top was exchanged in replace of a pointed tip. The monument was completed in its entirety in 1884, when an aluminum tip was placed on the top. Today, the monument stands as a symbol of American democracy and in recognition of first president George Washington, as the Washington National Monument Society had intended. It’s just how it came to be that make for quite an interesting story.

Washington Monument, NPS Contributors. NPS.com, History & Culture, 26 August, 2019.